Suppose you are in a spacecraft near a black hole, hovering at a fixed distance thanks to your engines. A fellow astronaut conducting repairs to the exterior of the spacecraft has a mishap ... and plummets towards the hole.

As you watch them fall, you never actually see them pass through the event horizon. If they’re carrying a flashing light, you will see that light grow dimmer and redder, and to you it will appear to be flashing ever more slowly as it approaches the horizon. You might even imagine that they’ve become frozen in time (as you measure it), granting them a miraculous reprieve by giving you as long as you need to rescue them.

But that’s not the reality at all! Although the light emitted by your unlucky companion as they approach the horizon will take ever longer to reach you, there is a finite time from the moment they fell until the moment when it becomes physically impossible for you to swoop down and snatch them back to safety before they cross the event horizon. If you wait any longer than that before you act, even a beam of light you sent after them wouldn’t catch up with them before they were inside the black hole – and your spacecraft certainly can’t do better.

How can we compute this time interval? A convenient set of coordinates to use for this problem are the Eddington-Finkelstein coordinates[1]. The space-time metric for a non-rotating black hole of mass M (using geometric units in which the gravitational constant and the speed of light are both equal to 1) is given in these coordinates by:

g = –(1 – 2M/r) dV2 + 2 dV dr + r2 (dθ2 + sin2 θ dφ2)

Here r is the Schwarzschild r coordinate, defined so that the area of a sphere of constant r has area 4πr2, θ is an angular coordinate measured from some chosen axis, and φ is an angular coordinate measured around the axis.

V is a time coordinate, chosen for the very useful property that for a ray of light falling straight into the hole, the value of V is constant. If we can derive the trajectory of our infalling astronaut as a function V(r), then since the event horizon is at r=2M, the value V(2M) will be the V coordinate of the last infalling ray of light that can reach the astronaut before they cross the horizon. It’s then easy to use the metric to compute the amount of time that passes for the spacecraft, at r=r0, as V advances from V(r0) to V(2M).

The easiest way to get a differential equation that we can solve to obtain the trajectory is by making use of the fact that the vector field ∂V is an isometry: if you shift every point of spacetime by increasing its V coordinate by the same amount, this has no effect on the geometry. This is obvious when you look at the metric, because none of its components are functions of V. As a consequence, the dot product between a unit-length tangent along a geodesic and ∂V will be constant along the whole geodesic.[2]

If we work with variables v = V/M and ρ=r/M, the constant M disappears from the equations, so we can solve them in all generality without needing to worry about black holes of different masses. The differential equation for v(ρ) that we obtain by requiring the unit-length tangent to the trajectory to have a constant dot product with ∂V is:

ρ2 ρ0 + 4 ρ (ρ0 – ρ) v'(ρ) – 2 (ρ – 2) (ρ0 – ρ) v'(ρ)2 = 0

Here ρ0 = r0/M is the value of ρ from which the astronaut begins their fall. This equation can be solved in closed form:

v(ρ) = ρ – ρ0 + √[ρ (ρ0 – 2) (ρ0 – ρ)]/√2

+ (ρ0 + 4) acos[2 ρ/ρ0–1] √(ρ0 – 2)/(2 √2)

– 2 log[ρ0 (ρ0 – 2)] + 2 log[2 √(2 ρ(ρ0 – 2) (ρ0 – ρ)) + ρ (ρ0 – 4) + 2 ρ0]

The constant of integration has been chosen so that v(ρ0)=0. We can then compute:

v(2) = (ρ0 + 4) acos[4/ρ0–1] √(ρ0 – 2)/(2 √2) + log[64/ρ02]

Finally, we multiply this by a factor of √(1 – 2/ρ0) in order to give the elapsed proper time back at the spacecraft, divided by the mass: this is the quantity τ/M plotted on the graph.

As a check, the corresponding classical result is plotted as well. This assumes Newtonian gravity, but still measures the time until a ray of light could catch up with the falling astronaut before they reached the same point, r=2M. The Newtonian calculation is based on conservation of energy (in fact so is the relativistic one, with the dot product between the falling body’s relativistic momentum and ∂V acting as a kind of conserved relativistic energy). Equating the kinetic energy to the change in potential energy gives us:

½ (dr/dt)2 = M/r – M/r0

½ M2 (dρ/dt)2 = 1/ρ – 1/ρ0

M dρ/dt = –√[2 (1/ρ – 1/ρ0)]

(1/M) dt/dρ = –√[½ ρ ρ0 / (ρ0 – ρ)]

This is solved by:

t(ρ)/M = (ρ03/2/√2) (√[ρ (ρ0 – ρ)]/ρ0 + acos[√(ρ/ρ0)])

The dashed curve in the plot at the top of the page is t(2)/M – (ρ0–2), i.e. the time of arrival of the falling astronaut at r=2M, minus the time it would take for a message at lightspeed to reach r=2M from r=r0, all divided by M.

Somewhat surprisingly, the full, general-relativistic analysis yields exactly the same differential equation for the proper time τ experienced by the falling astronaut as we just obtained for the Newtonian time, and hence the same result:

τ(ρ)/M = (ρ03/2/√2) (√[ρ (ρ0 – ρ)]/ρ0 + acos[√(ρ/ρ0)])

So the time measured by the falling astronaut until they pass through the horizon looks very similar to the dashed curve for the Newtonian time-for-rescue, only differing by the linear term ρ0–2 that no longer needs to be subtracted.

Suppose you’re too late to rescue your friend before they pass through the event horizon. How much time do you have to send a parting message to them at lightspeed that will reach them before they hit the black hole’s singularity at r=0? Of course in most black holes they’d be killed by tidal forces long before that happened, but in a giant black hole they might get quite close to the singularity.

We can plug r=0, or equivalently ρ=0, into our formula for v, to obtain:

v(0) = π (ρ0 + 4) √(ρ0 – 2)/(2 √2) – ρ0 – 2 log[(ρ0 – 2)/2]

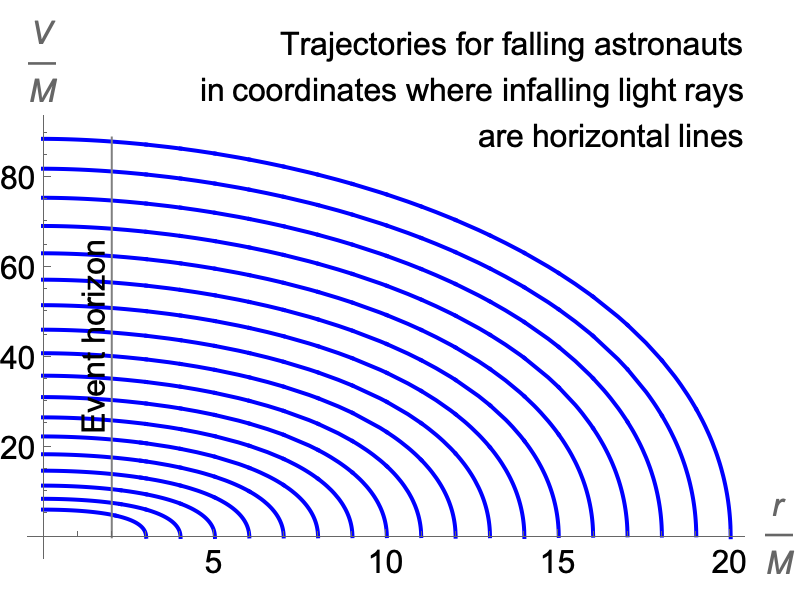

As before, we need to multiply this by a factor of √(1 – 2/ρ0) in order to give the elapsed proper time back at the spacecraft. It’s clear from the plot of trajectories of falling astronauts that these times are finite, and proportionately not much greater than the times to the horizon.

The time experienced by the falling astronaut before they hit the singularity is easily found from the last formula of the previous section:

τ(0)/M = π ρ03/2/(2 √2)

On a more optimistic note, suppose you do act quickly enough to reach your falling friend. If we care about the time that passes at the spacecraft’s original location, r=r0 (as opposed to the time you personally experience during your rescue mission) it’s not hard to show that this can increase without bound. Your spacecraft can’t do any better for the round trip than two beams of light: one that travels in and catches up with the falling astronaut, and another that immediately comes back in the other direction.

The ingoing null geodesics in Eddington-Finkelstein coordinates take the simple form V=constant. From the metric, we can check that outgoing null geodesics will satisfy the equation:

dV/dr = 2r/(r – 2M)

Switching to the simpler variables where we divide everything by the mass of the black hole, v = V/M and ρ=r/M, we get:

dv/dρ = 2ρ/(ρ – 2) = 2 + 4/(ρ – 2)

This equation is solved by:

vON(ρ) = 2ρ + 4 log[ρ – 2] + C

where we’re writing vON(ρ) for the outgoing null geodesic, to avoid confusion with our previous function v(ρ) for the infalling astronaut.

If you take a certain time τR to respond to the fact that your companion has fallen, the soonest you could possibly reach them is at the event where an ingoing light ray would reach them, for which the v coordinate is given by:

vR = (τR/M) / √(1 – 2/ρ0)

The value of ρ at which the ingoing light ray would reach the infalling astronaut would be the ρR that solves the equation:

v(ρR) = vR

We can’t get an explicit formula for ρR, but if we find the value numerically we could then plug it into our equation for the outgoing geodesic to solve for the constant C that identifies the particular light ray we’re interested in:

vON(ρR) = 2ρR + 4 log[ρR – 2] + C = vR

C = vR – 2ρR – 4 log[ρR – 2]

Now we can find the v coordinate for the outgoing light ray when it arrives at r=r0:

vON(ρ0) = vR + 2 (ρ0 – ρR) + 4 log[(ρ0 – 2)/(ρR – 2)]

The longer you wait before responding, the closer the falling astronaut will be to the event horizon when you reach them – or in the best-case scenario, when an ingoing light ray would reach them. And as ρR gets closer to 2, the last term above increases without bound.

So the time back at the spacecraft’s original position (as measured, say, by the crew of a second craft that didn’t take part in the rescue) increases without bound, as a consequence of a finite delay in your response. In other words, once vR=v(2) the rescue is literally impossible, but even as vR gets close to v(2), the rescue can entail arriving back where you started after an arbitrarily long time has passed for the astronauts who stayed put.

Of course, for you the time experienced during the rescue can be greatly reduced by relativistic time dilation, but that doesn’t change the fact that there’s an unmissable deadline at the start of the process.

|

|

As we mentioned at the start of this page, if your companion free-falls towards the black hole while you remain at a fixed distance from it — thanks to your spacecraft’s engines — you would see a flashing light they are carrying grow redder, and flashing more slowly. Of course, if you use the spacecraft to swoop down to catch them, once you are beside them and matching their velocity (anything less would make for a bruising encounter rather than a smooth rescue), the light you see from them will be perfectly normal. The exact course of the transition, in which the redshift disappears, will depend on your precise trajectory.

In this section, we will describe something simpler: how will the light from your falling companion appear to you if, after some delay, you fall towards the hole yourself?

(As ever, we are ignoring the question of exactly when tidal forces from the black hole would rip any actual observer apart, in favour of a thought experiment where light is emitted and received by indestructible point sources and detectors.)

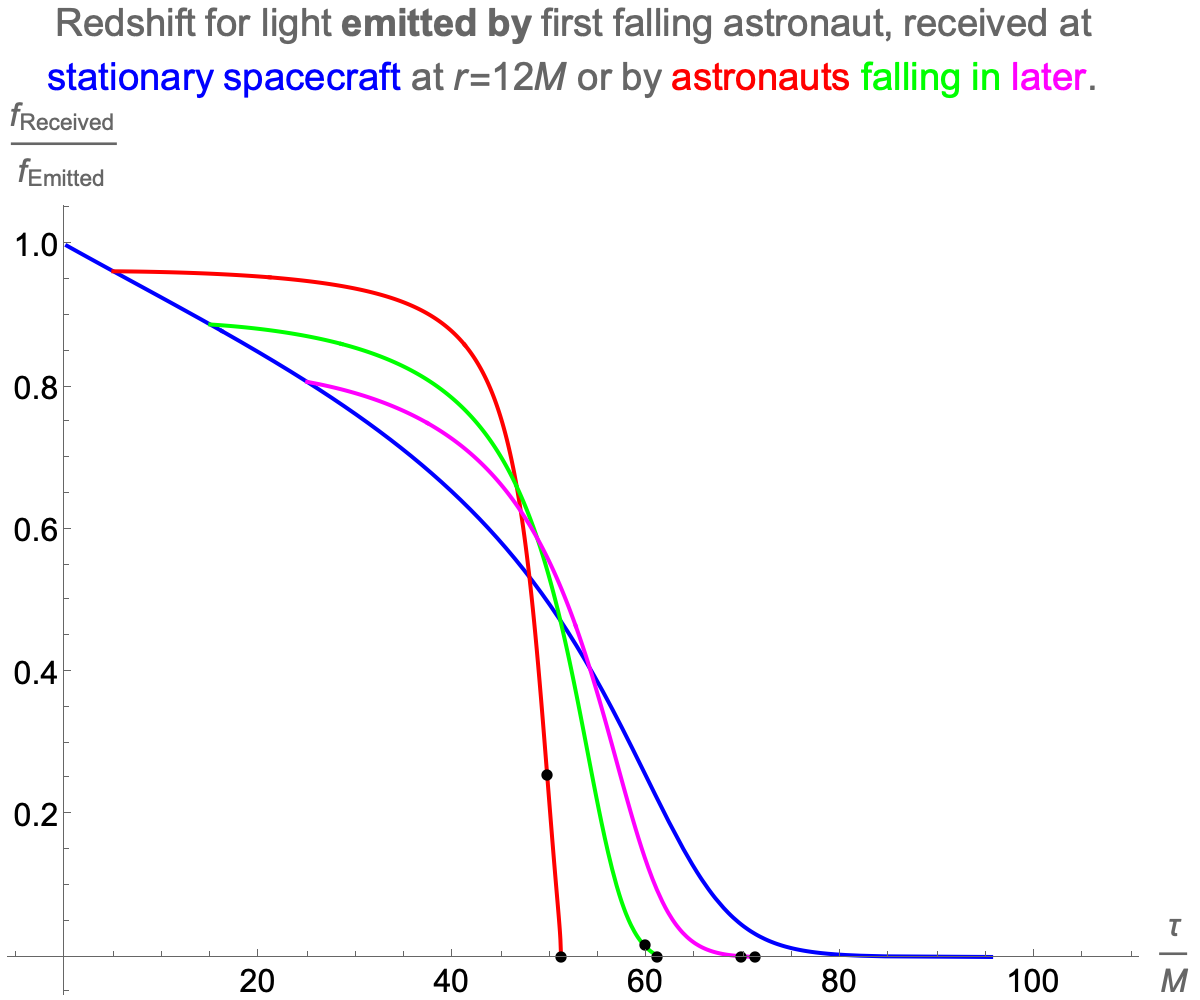

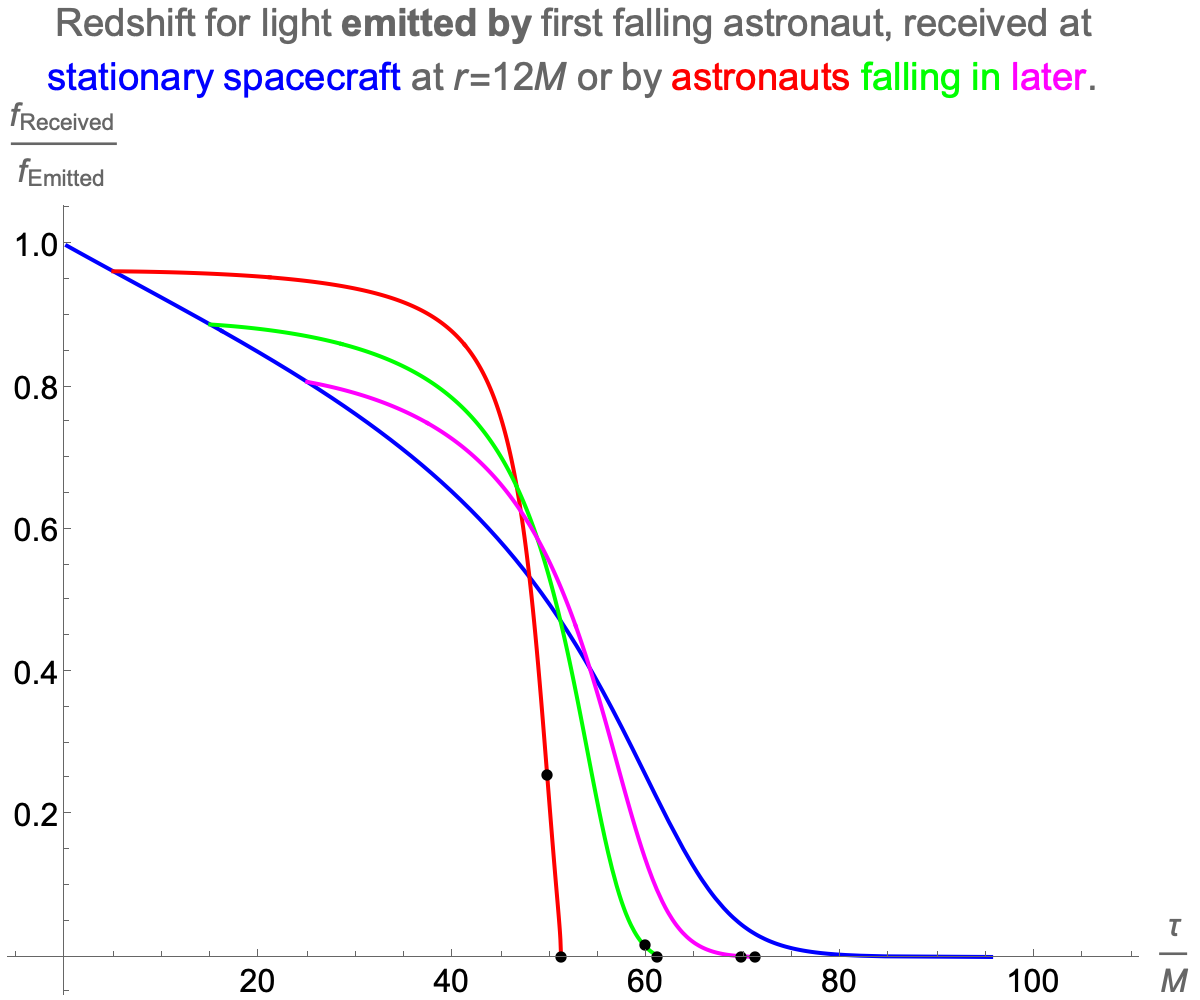

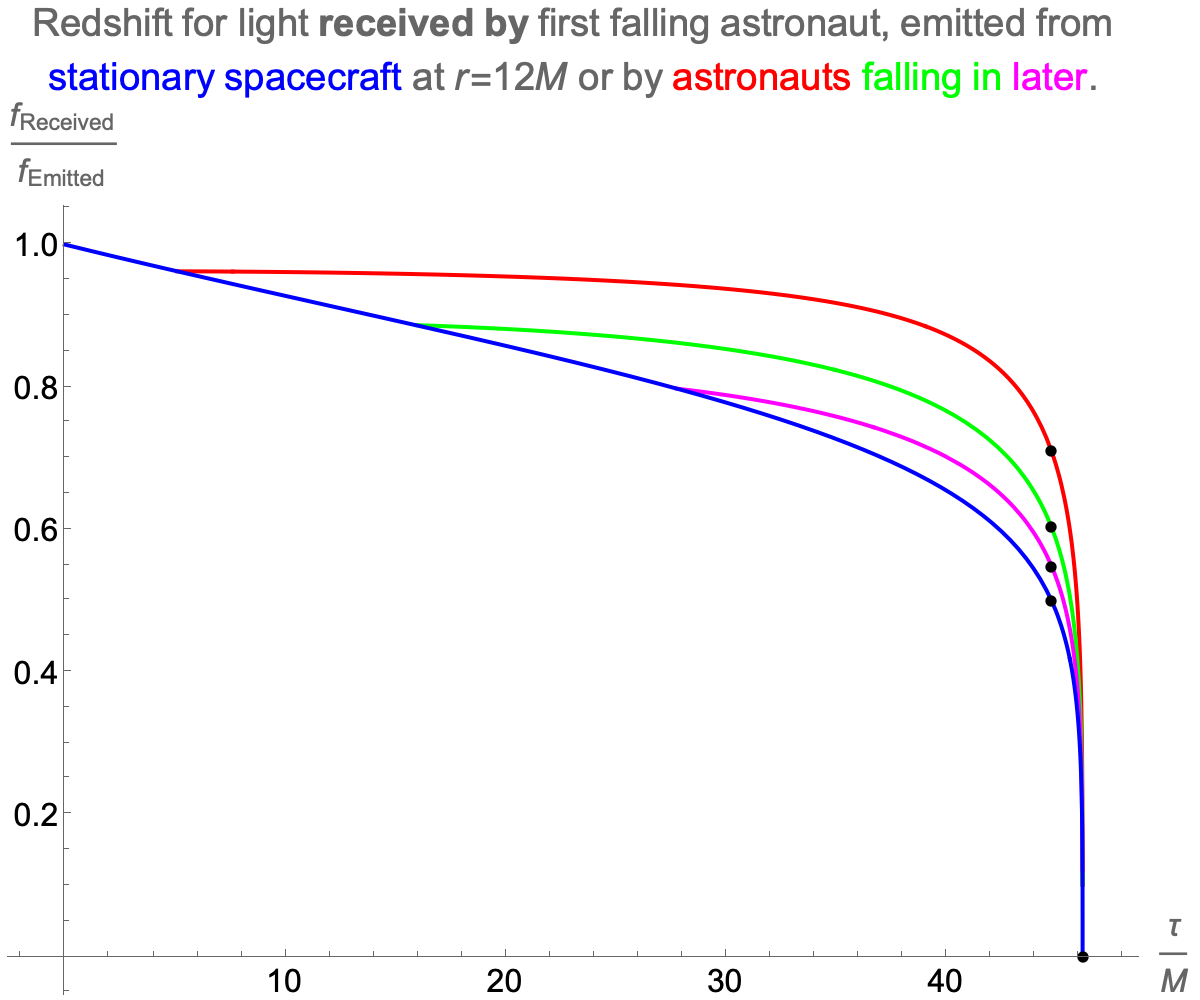

In the image on the top right, the redshift is given as a factor by which the frequency of light emitted by the first falling astronaut is reduced when observed by the second astronaut. The main curve plots the value of the redshift if the second astronaut simply stays on the spacecraft, while the offshoots show what happens if the second astronaut also jumps, after three different delays.

The time along the horizontal axis represents the proper time passing for the second astronaut. The points where the second astronaut crosses the horizon, and when they hit the singularity, are marked on the curves with black dots. No light can pass outwards through the event horizon, so the light received by the second astronaut before they fall through the horizon must all have been emitted by the first astronaut before they fell through it — and the light received by the second astronaut at the instant they cross the horizon must have been emitted by the first astronaut at the (earlier) instant when they crossed it.

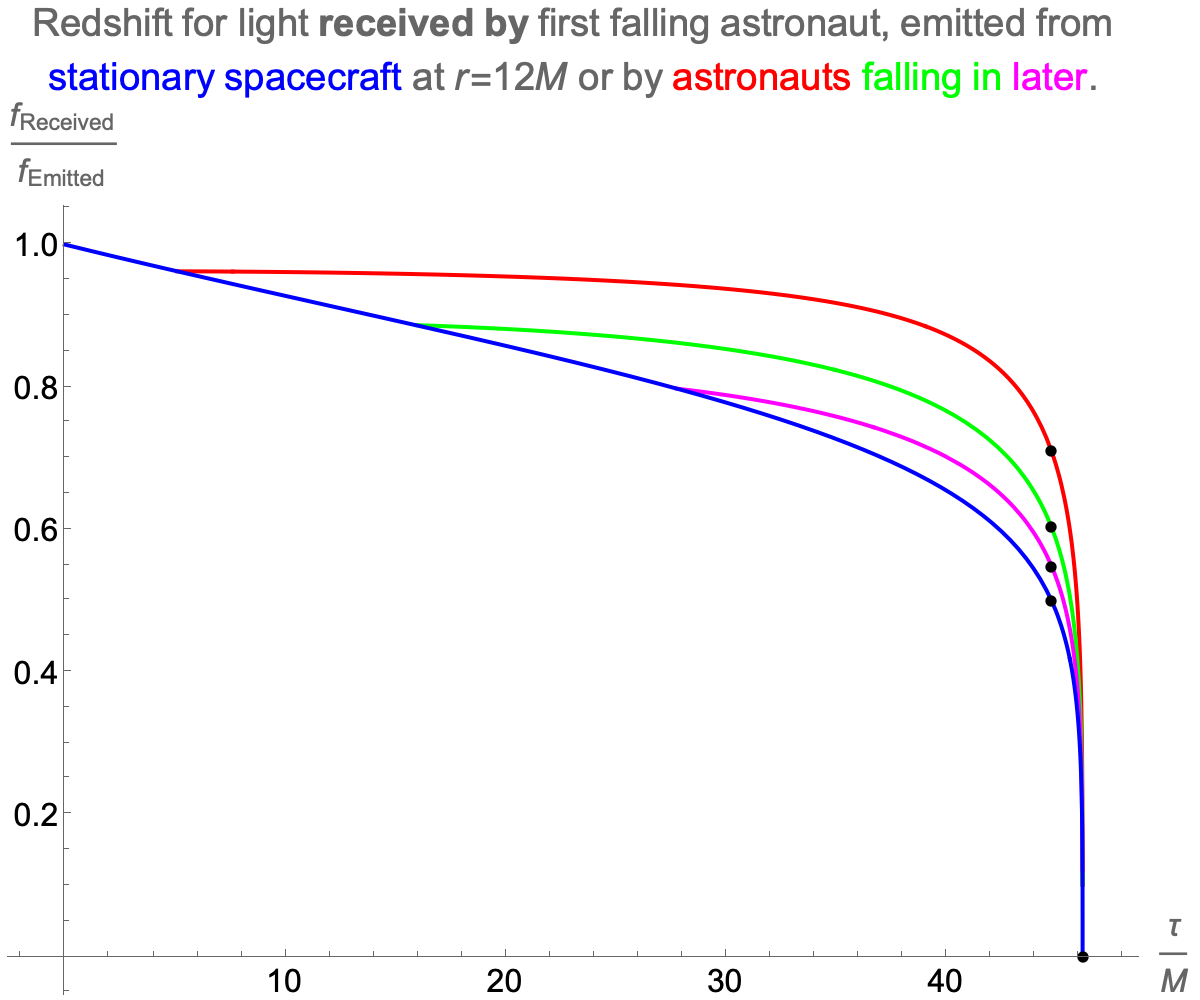

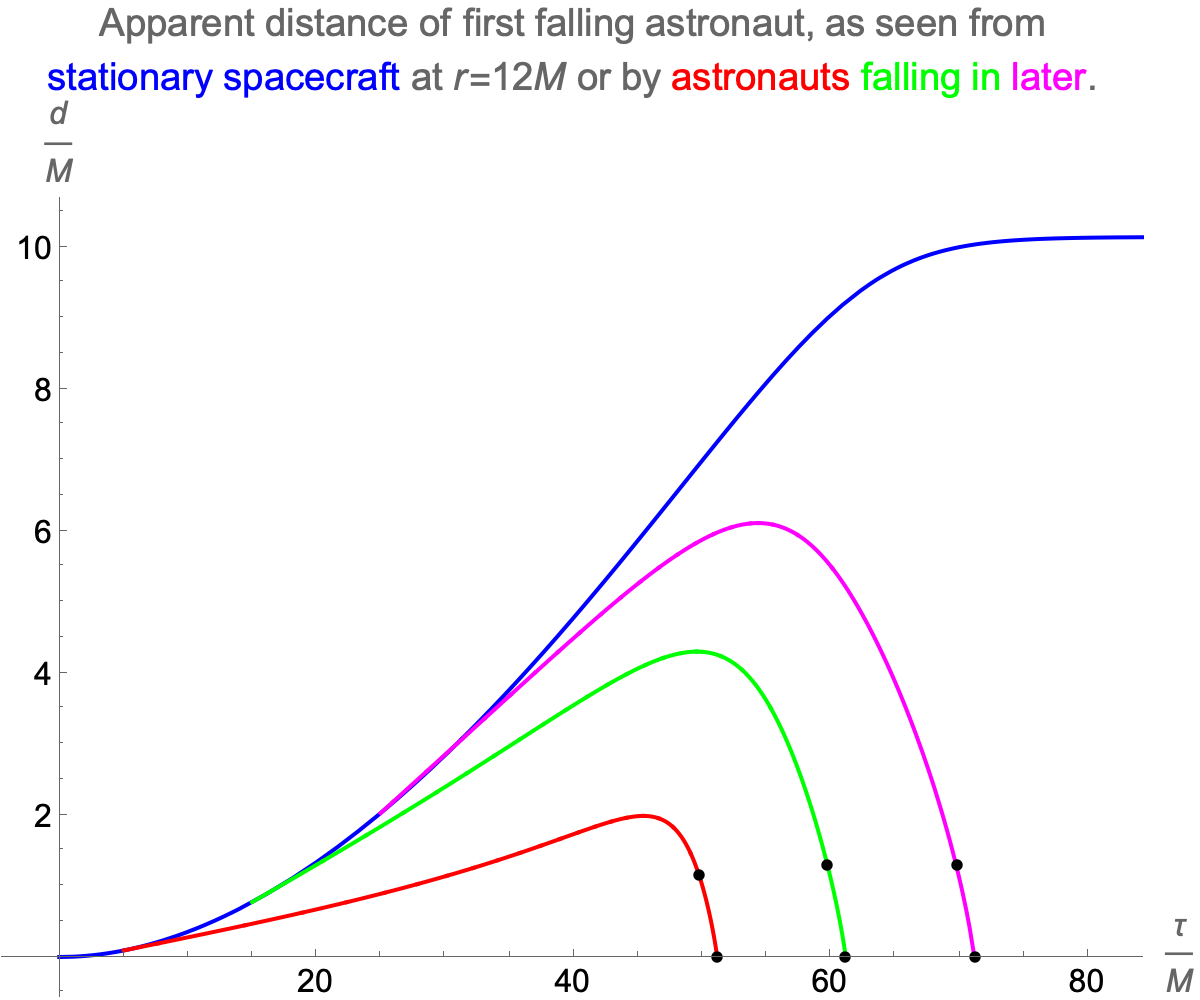

In the image on the bottom right, we plot the redshifts that the first falling astronaut measures for light they receive: from the spacecraft remaining at a fixed distance above the black hole, and from astronauts who fall in afterwards, in the same scenarios as for the first plot.

The black dots on the curves here mark the first falling astronaut crossing the event horizon, and hitting the singularity. Unlike the previous plot, where the light is travelling outwards, the incoming light that the first falling astronaut sees as they cross the horizon is emitted by the other astronauts while they are still outside the black hole. And in the scenario we have chosen, the first falling astronaut hits the singularity before receiving light from any of the others as they cross the horizon.

As well as measuring the redshifts, we can ask what the “apparent distance” is to the first falling astronaut, either as seen from the spacecraft, or by astronauts who fall in later.

The distance between objects that are widely separated and moving at relativistic speeds through highly curved spacetime has no definition that is independent of the way we choose to carve up spacetime into space and time, but we can define the “apparent distance” in purely observational terms: if the observer was able to measure the parallax — the change in the angular position of the falling astronaut from two vantage points displaced to the left and right by a known distance in their own rest frame — then, given that baseline and parallax angle, what distance would they compute for the object they were looking at, if everything was at rest in flat spacetime?

The image on the left plots these distances to the first falling astronaut, as measured by observers on the stationary spacecraft, or by astronauts who fall in later. The black dots here mark the points where the second astronaut crosses the horizon, and when they hit the singularity.

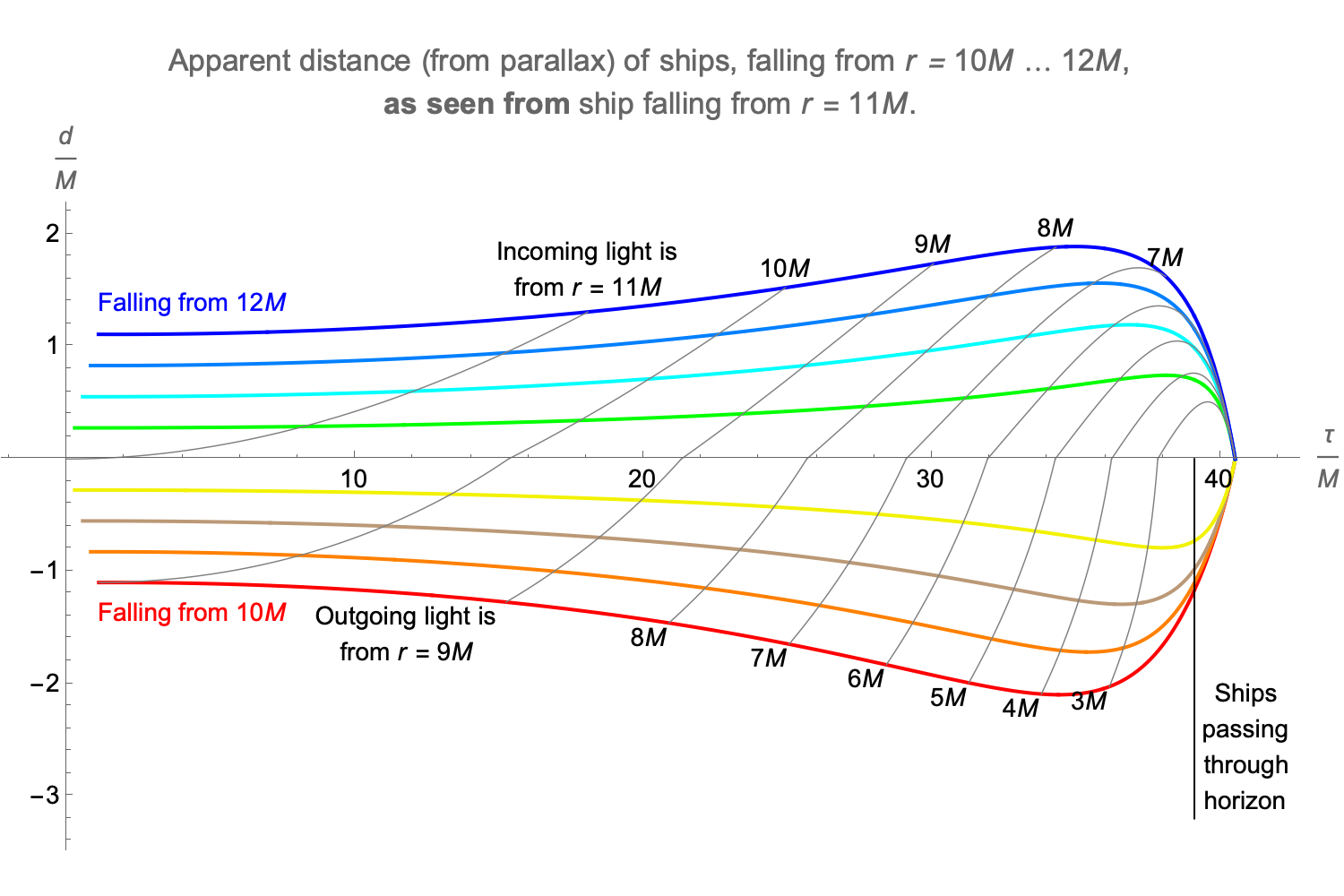

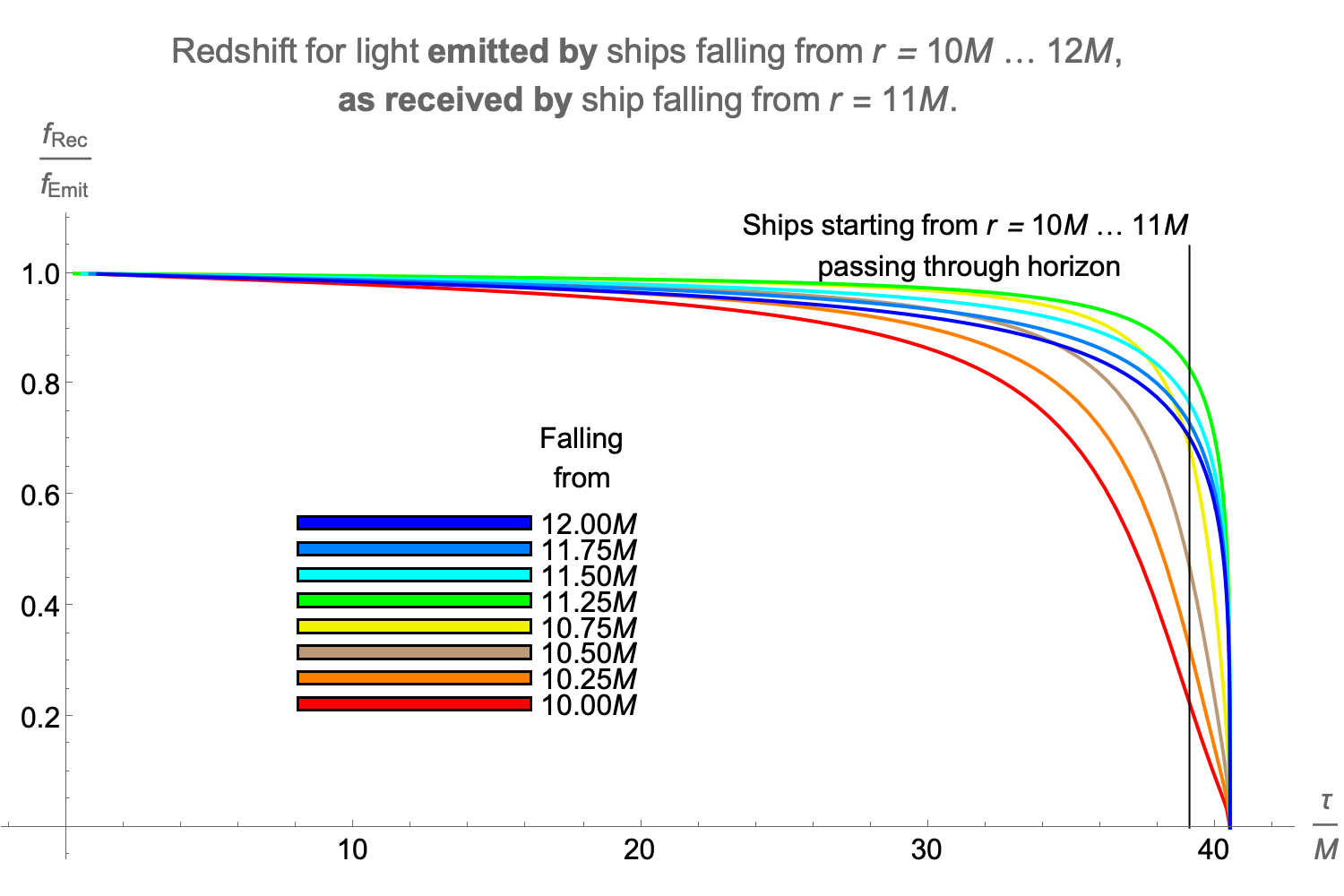

To give one more example (and to answer a question posed by John Baez), suppose a fleet of nine ships all fall from different radial coordinates, ranging from r = 10M to r = 12M, starting their fall at the same Schwarzschild time coordinate t.

The image on the top right shows the apparent distances to the other eight ships, as measured by parallax on the ship in the middle of the fleet (which fell from r = 11M). The grey lines crossing the diagram mark various values of the r coordinate where the ships were located when the light currently received from them was emitted.

The image on the bottom right shows the red shift for light emitted by the other eight ships, when received by the ship in the middle of the fleet.

Our formula for outgoing light rays:

vON(ρ) = 2ρ + 4 log[ρ – 2] + C

makes it clear that there is no bound on the time it can take, back at the spacecraft, to receive light sent by the infalling astronaut just before they cross the horizon. This is one source of the tempting misconception that the falling astronaut is somehow “frozen” at the horizon.

If light from the falling astronaut can be misleading, what if we ignore that and instead think about the way a stationary astronaut might try to extend their local notion of “space, at this moment”? A simple calculation allows us to compute the family of spacelike geodesics that are orthogonal to the world lines of anyone with a fixed r coordinate. In this case, the dot product with ∂V along the geodesic has a constant value of 0, and the differential equation we need to solve is:

vSP'(ρ) = ρ/(ρ – 2) = 1 + 2/(ρ – 2)

The solutions are:

vSP(ρ) = ρ + 2 log[ρ – 2] + C

These are plotted in the diagram on the right.

Even though these geodesics extend to “infinitely negative time” while remaining outside the horizon, their proper length measured from any finite starting point ρ0 outside the black hole, up to the horizon at ρ=2, is finite:

sSP(ρ0) / M = √[ρ0 (ρ0–2)] + log(√[ρ0 (ρ0–2)] + ρ0 – 1)

If we consider the sequence of geodesics that intersect the world line of the stationary astronaut at regular clock ticks, the infalling astronaut will cross an infinite number of them before crossing the horizon — illustrating another sense in which the fall might be considered “infinitely prolonged” according to observers who remain at a fixed distance from the hole. But the time limit on any kind of rescue – or even sending a message at lightspeed to the falling astronaut – makes it clear nonetheless that in every physically meaningful sense the fall is finite.

[1] Gravitation by Charles Misner, Kip Thorne and John Wheeler, W.H. Freeman, San Francisco, 1973. Section 31.4.

[2] op. cit. Section 25.2.